Thalia walks the beach each day. She goes at dawn when the sun pinks the sky behind the hills and dew pearls the grass along the roadside. The beach is small and narrow, nestled between two outcrops of rock where seals bask with their pups. Low tide doesn’t add much to the beach’s depth. It leaves a ribbon of clean, dark sand, edged by a fringe of light gravel and broken shells. The high tide mark sits above a band of pebbles and stones, some large and immovable, often decorated with strands of seaweed or discarded nets and rope. When there is a storm, the wild Atlantic waves crash up beyond the sand, pushing a wind-whipped froth across the road and into the gardens of the tourist cottages. Most locals know better than to go down to the sea in a storm but fair weather or foul, Thalia walks the beach each day.

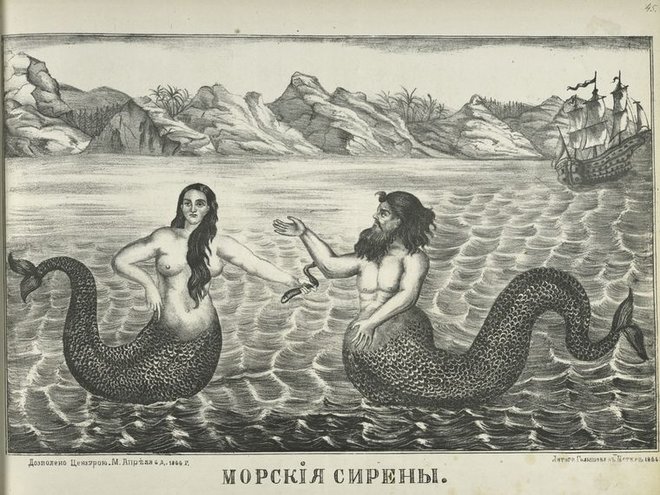

Before Douglas went missing, Thalia would scour the beach for glass, shards of broken pottery, and shells. In her studio in the garden shed, she’d sort and arrange her treasures, by material, size, and color. On her bench she’d make mosaics of island life to sell in the tourist shops: seascapes with the islands on the horizon, colorful boats in the harbour, tropical fish never found in the cold waters of the Atlantic. Her most recent and ambitious work was of a mermaid and merman floating in a sea of blue and green glass. When Thalia walks on the beach now, her gaze never leaves the ocean where she searches for treasure more precious than broken glass.

Days pass in a storm of grief when Thalia feels the breath stolen from her lungs by the pain of Douglas’s absence. She weeps and pleads with the sea to return Douglas, that her need for her husband is far greater than the whim of the undertow. But her tears fall into the ocean and are subsumed in the brine.

Days merge into weeks and the grief transforms into waves of pain. Thalia oscillates between feeling like her life is under the ocean with Douglas and that she could – and should – go on living, an amphibious creature belonging to land and sea and neither.

Weeks become months, Thalia is becalmed, afloat in the doldrums where neither winds nor tides reach her. Her gaze returns to the sand beneath her feet, seeking glass gems more from habit than want. She resumes her work in the shed and slowly, as her mer-couple emerges on her workbench, she feels herself transforming into something new. Her belly rounds, her skin glows, and she replaces coffee with lemon and ginger tea.

One morning, five months or so after Douglas’s disappearance, Thalia goes down to the beach to search for sea glass. She finds her eyes drawn to an unusual shape on the sand, just above the low tide line. It is as she bends down to pick it up that she first feels the quickening in her belly, a flickering sensation that reminds Thalia of a funfair goldfish, caught in a too-small jam jar. Instinctively, her hand goes to stroke the spot where she thinks her prize would be and it isn’t until she gets home and empties her pockets that she sees that the object she had picked up from the sand was a bone, a knobbly vertebra, spiny protrusions reaching out from a stubby tube.

She had always believed the spoils from her daily walks to be gifts from the ocean, left on the beach for her to find and repurpose, and it occurs to Thalia that the bone is left just for her, a gift with a meaning only she can fathom. Could it be that the ocean had recognised the particular salinity of her tears, heard her cries, and believed her when she said she’d give anything – everything – to have Douglas back on shore with her again?

That night Thalia feels Douglas’s absence more than she has since the sea had taken him. Their bed feels too big and empty for only her frail body. She lies awake, her mind torn between the bone left on her workbench, the all-powerful ocean, and the new life swimming within her. She falls into a fitful sleep an hour before dawn and dreams of mermaids calling her husband to join them beneath the waves.

Thalia wakes late and goes straight to the beach where she combs the sand for more bones. She is certain now that the ocean is returning Douglas to her, perhaps not in the way she expected or wanted but who was she to make demands of the sea? And so she sifts the sand between her fingers, she rakes the pebbles, first with sticks, then with fingers bloodied by the sharp edges, and she finds what she seeks.

There are days when all she brings home are regret and despair, but there are other days when her pockets are filled with flute-like ribs, yellowed femurs, and brown teeth that look older than the ocean itself.

Thalia shoves the mer-people mosaic off her workbench. It lies on the shed floor, unfinished and broken. In its place, Thalia begins to assemble the bones.

It isn’t easy. When she makes a mosaic, she tries to create an approximation of her subject. So long as she is true to its proportions, she knows the human mind will fill in the details. When she makes the image of a boat all she needs do is keep true to its shape and suggest a sail. Viewers will bring the noise of that sail’s snap in the wind and the shadow of the gulls circling overhead. Making a man needs more than artistry. She needs biology and engineering and perfect adherence to a divine design.

As new life grows within her, Thalia keeps searching for the cogs and gears she needs to rebuild Douglas. She searches the internet for images of a man broken down to his component parts and prints off blueprints to pin to the wall for easy reference.

As she sifts through sand and shingle she remembers that everything she takes home from the beach is a gift from the ocean, be it bone or bivalve, muscles or molluscs. Until now, Thalia has hesitated to bring home soft tissue gifted by the sea. Its sliminess and stench made her retch and dance her fingers around its gelatinous mass. But Douglas was made of more than bone. He was flesh and blood and bone. Next day, Thalia brings rubber gloves and a lidded plastic box to the beach and accepts all the deep’s bounty. She stores the boxes in her freezer to keep fresh until she needs them and soon there is no room in there for food.

Each evening she sits at her workbench to assess her progress and as it gets nearer the time when she must launch her child, she notices how her progress slows.

New-Douglas’s form lies on the bench, his head facing the window where it can watch the setting sun. Thalia has given him shells for ears and salvaged glass marbles shine dully where his eyes should be. Dried grasses lie haphazardly around his face, their yellow close to the dirty blond mop Thalia wound around her fingers when they kissed. His teeth are a curious collection of brown and yellow molars and incisors that Thalia has brushed with the toothbrush he had left behind. Under the grasses, Thalia has used all her creativity to form a mind. A dictionary lies beside a tide table; a CD Mix tape of his favourite music balances on his favourite aftershave; a souvenir Eiffel Tower from their first holiday together, a plastic toy fishing boat, a small jar of honey from his parents’ farm, an OS map of the village, his grandfather’s watch, all packed between his shell-ears.

Thalia is happy with what she has so far but knows she is a long way from finished. As she assesses what is still missing from not-Douglas-yet she is cut in two by the worst physical pain she has ever felt and a trickle of warm liquid runs down her legs, pooling on the slate workroom floor. Thalia knows she has only a little time to complete her work, and between surges of pain, she brings the plastic boxes from the freezer and arranges the guts and entrails and small carcasses she harvested from the beach around the pelagic skeleton she has assembled.

A sudden storm blows in off the sea, rattling the thin glass of the shed window and pushing icy fingers through the gaps, wailing like sirens calling Thalia to join them in the roiling waves. Thalia grabs the edge of the bench and screams; she screams for Douglas, she screams for the sirens to leave her alone, and she screams at the pain that she’s sure will cleft her in two. The pain swells and retreats like the waves on the beach, each one bringing her closer and closer to a precipice she knows will either kill her or save her. As she pants and pushes, she doesn’t care which.

Squatting on the floor, among shells, stones, sea glass, and dirt, Thalia braces against the pain and pushes and strains until she feels she can do no more. She looks up to see almost-Douglas lit up by a fork of lightning that finds earth just beyond the beach. Her husband seems to shudder in the flickering light and Thalia, reenergised, gives one final push. From between her legs slips a membrane, bloodied yet intact. Inside is a creature curled to fit inside its aqueous cocoon, its limbs destined for a life she is unable to give it. A mermaid baby, unwilling to leave the watery confines of its caul.

Thalia gazes at the baby and knows what she must do. She uses a knife to sever the tether holding it to her and after delivering the placenta, she wraps her child in her apron, placing it gently back on the slate. She takes the placenta and rests it over soon-Douglas’s heart space and places a kiss where his lips should be before picking up the mer-child and staggering to the beach. There, in the intermittent moonlight, she wades into the icy ocean and offers the child to the mermaids in exchange for her husband. She places it in the ocean with a mother’s gentleness and watches as it’s taken from her and carried to its new home.

Thalia turns and without looking back, makes her way up the beach to the cottage where she climbs into bed, still clothed in her bloodied and sea-washed dress. She knows she can do no more and believes that Douglas must come to her now. She closes her eyes and as she falls asleep, she’s sure she hears a familiar creak on the stairs, and the mattress behind her sink with the weight and briny scent of her husband.

(Originally published in Cersarus Magazine in January 2023)

Leave a Reply